How we learned to sail

I believe Mary and I were somewhat adventuresome because we went out and purchased our first sailboat than proceeded to learn how to sail. I had the benefit of some earlier sailing experiences as a passenger in my youth, which helped in understanding the fundamentals of sailing. Mary (my first mate) had been a passenger on several occasions so she had some comprehension of the process.

As chance would have it, we started our sailing career by launching our Mac25 in Newton, MA on the Charles River on July 4th, 1997. We were bare poled (no Mast or sails) because we had to pass beneath several very low overpasses as we motored our way to the fireworks on the Esplanade. There were five of us on board for the weekend. We were a heavily ballasted, low speed, fully packed motor boat. Granted, this is not sailing but it gave us a chance to become familiar with the operation of all non-sailing systems on the boat. It also taught us about the limitations of the boat when five adults sleep on board all night during 15-20 knot winds and expect reasonable creature comforts and a hot meal in the morning. I also quickly learned about proper anchoring techniques and having sufficient scope extended for an all night grip into the muck on the bottom of the Charles River.

We ventured forth several more times the first season but I felt uncomfortable by our lack of experience and how to handle navigating. We also had very little command of the sailing terminology. Plus, my first mate didn’t feel qualified to take over in case of an emergency. Here is where the US Coast Guard Auxiliary enters. Let me preface the following several paragraphs by saying… hats off to the all volunteer, uniformed USCG Auxiliary. Don Melanson and Larry Nobrega did an excellent job in presenting the information and representing the USCGA.

We both started a 13-week course on Sailing and Seamanship. This was three hours per week in an academic setting, which covered 14 chapters of information. It culminated with a written and graded final examination. It was a humbling and enjoyable experience for both of us. We covered:

1. What makes a Sailboat?

One of the most fundamental concepts that we needed to understand is what makes a boat sail. If you understand why an airplane flies this is much the same. Air passing over the sail or over the wing creates a low- pressure area on the reverse side. This happens because of the curvature of the sail or curve of the airfoil. The low-pressure area actually pulls you along in a boat or lifts you if you’re flying. In a boat, the keel keeps you from slipping sideways too much and yields a resultant force forward which moves the boat. Understanding this makes trimming the sails and basic maneuvering more easily understood.

Another topic which proved very useful was Marlinspike Seamanship. This is the art of working lines and making various knots for the correct situations. The most useful knots turn out to be the overhand, half hitch, clove hitch and above all else the bowline. We learned that the definition of a good knot is one that is strong for the application but is easily taken apart when necessary. That’s a very nice feature of the bowline.

Throughout the course we were constantly expanding our vocabulary of nautical terms. Initially it was not clear why there was so much unique terminology. As an example, there are virtually no ropes on a boat. Once a rope come on a boat it becomes a line. Types of lines include: halyards, sheets, bow line, hawser, jib sheet, outhaul, reef points, spring lines and more. The reason for the terminology is so that in critical sailing moments the captain can give a command with clarity and brevity. And critical moments do seem to occur when least expected.

Navigation techniques were also very important. How to read coastal maps is very useful. Plotting a course, navigating to a specific destination and having an understanding of all the nautical aides available (buoys, lights, bells, etc) are critical for off shore sailing. Although a GPS is a marvelous invention, the traditional navigation skills are more reliable.

Upon completing this USCGA course we had a much better appreciation for sailing techniques and a healthy respect for some of the dangers. But learning to sail cannot be totally learned in the classroom.

We learned the most effective technique for refining our skills was to invite sailing friends with more advanced skills. This worked wonders on rapidly learning how to trim the sails and bolstered our confidence in our abilities.

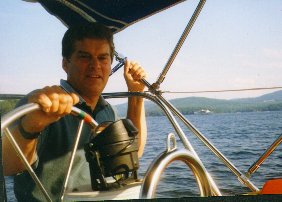

Three years have now passed and we get great satisfaction working as a team. Generally, Mary is at the wheel as the first mate and I plan the maneuvers and work the sails. We have learned the value of teamwork and thoroughly enjoy the process.